This is a follow-up to my earlier entry on Bullinger's Mariology.

Over the years I've witnessed Rome's defenders saying that Protestant Reformer Heinrich Bullinger believed in the Assumption of Mary. As far as I can determine, the most important evidence for this conclusion appears to be based on merely one Bullinger quote:

"Elijah was transported body and soul in a chariot of fire; he was not buried in any Church bearing his name, but mounted up to heaven, so that on the one hand we might know what immortality and recompense God prepares for his faithful prophets and for his most outstanding and incomparable creatures, and on the other hand in order to withdraw from men the possibility of venerating the human body of the saint. It is for this reason, we believe, that the pure and immaculate embodiment of the Mother of God, the Virgin Mary, the Temple of the Holy Spirit, that is to say her saintly body, was carried up into heaven by the angels."

This quote can be found in a variety of forms, documented (if at all!) in different ways. Often the quote is dated only a short time before Bullinger's death, in 1568, in which case, Bullinger held to Mary's Assumption for almost the entirety of his life. Rome's defenders often use snippets of information like this to provoke historical dissonance in dialog with Protestants: the Reformers believed in

sola scriptura, yet believe

x y or

z about Mary...

so why don't you? In what follows, I'd like to demonstrate that Rome's defenders sometimes aren't up front with all the facts, and when those facts are presented, a different scenario may indeed be possible in regard to Bullinger and the Assumption of Mary.

Documentation

Sometimes the quote above is documented with a reference to Max Thurian's

Mary, Mother of All Christians,

197-198. Thurian says in 1568 Bullinger wrote this comment on the Assumption of Mary. Thurian says he took the quote from Walter Tappolet,

Das Marienlob der Reformatoren:

Martin Luther, Johannes Calvin, Huldrych Zwingli, Heinrich Bullinger, p.327.

This pdf (with the Nihil Obstat and Imprimatur) cites the quote as "

On Original Sin, 16 (1568)." This is actually a reference to the chapter in the primary source,

De Origne Erroris, 16 from Bullinger. This documentation of the primary source may have originally come from Hilda Graef,

Mary, A History of doctrine and Devotion, p. 15. She likewise notes 1568, and also that she took the quote from Tappolet. This tedium points to one conclusion: the quote, in whatever form one may find it, will probably lead back to Tappolet's,

The Marian Praise of the Reformers.

Bullinger's Three Quotes on the Assumption of Mary: Developing to the Assumption?

I have a copy of Tappolet's book. It's more of an anthology of Marian quotes from the Reformers than an actual analysis of Reformation Mariology. Tappolet doesn't simply provide one quote from Bullinger on the Assumption of Mary, he provides three (p.327-328). He provides quotes from three different dates, in this order:

1552,

1565, and

1568 (the last quote being that cited above). If one uses the quotes presented in this order, it appears that Bullinger went from uncertainty about Mary's Assumption to certainty. In

1552, Bullinger says we simply know that Mary is in Heaven, and "

the Scriptures say nothing more" (The

1552 quote can be found here,

Von der Verklärung Jesu Christi). In

1565, Bullinger alludes to the testimony of Ephiphanius on the uncertainty of Mary's death, and states,

"It is quite dangerous to try to explore or explain for sure where the Scripture is silent!" (The 1565 quote can be found here ,

Epitome temporum). But then in

1568 he does an about face and states, "...

we believe, that the pure and immaculate embodiment of the Mother of God, the Virgin Mary, the Temple of the Holy Spirit, that is to say her saintly body, was carried up into heaven by the angels." The quote is authentic (

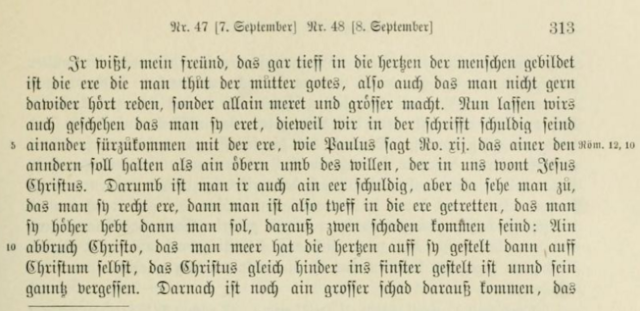

here is the page in the 1568 edition).

Something doesn't add up. If one looks closer at Tappolet's citations, he does preface the

1568 statement by saying, "

The strangest testimony of Bullinger's on the question of Mary's Assumption is contained in Froschauer's 1568 edition of De Origne Erroris Chapter 16" (p.328). Even Tappolet, the primary source for the quote realizes something isn't quite right. He then includes a few final comments of bibliographic tedium including the fact that the

1549 French edition of

De Origne Erroris deleted Bullinger's Assumption comment.

1549? Wasn't

De Origne Erroris written at the end of Bullinger's life in

1568? It wasn't. Bullinger composed this book much earlier (

1529; it was the companion volume to a book he wrote in

1528). Bullinger was 25 when he originally wrote this book. He revised these two volumes into one volume in

1539. It is in this

1539 edition that the Marian statement in question appears to have originally been written (

see page 45). I could not locate the quote it in the 1529 edition, nor do I know if he revised this book previous to the 1539 edition. So, the comment from Bullinger affirming Mary's Assumption precedes the two quotes in which he says one cannot affirm Mary's Assumption. In other words, the documentation points to Bullinger going from affirming the Assumption to being agnostic on the Assumption.

Conclusion

I've yet to come across one of Rome's defenders using the alleged

1568 Assumption quote in its historical lineage, either mentioning how something doesn't quite add up or placing it back in

1539 where it belongs. I've not come across one them saying, "

Bullinger earlier affirmed Mary's assumption, but then appears to become agnostic on it." Sometimes, they will come close. Peter Stravinskas, a bit more careful states,

Zwingli's successor, Bullinger, once confessed that Mary's "sacrosanct body was borne by angels into heaven," although he declined to take a firm stand on either her bodily assumption or her immaculate conception. [Thomas O'Meara, Mary in Protestant and Catholic Theology (New York: Sheed and Ward, 1965), 178-179]. [source]

So according to Straviskas, Bullinger once confessed Mary's Assumption, but didn't take a firm stand on it. This is true, as far as it goes. Certainly Bullinger did plainly affirm the Assumption in 1539, but contrary to Stravinskas, this was indeed a strong stand in 1539. It appears that only later did he decline to take a firm stand. Stravinskas may have never bothered to read the quotes in historical order so ended up describing a confused Bullinger.

Did Bullinger believe in the Assumption? It appears he did in 1539. He plainly states though in later writings that one cannot know Mary was Assumed into heaven. I see a development in Bullinger here. The entire sixteenth century church was

bathed in Mariology, so it would not be surprising to discover that Heinrich Bullinger didn't necessarily repudiate every aspect of it immediately. It would not be surprising as well to discover that as church history progressed from the Reformation, the

bath water of Mariology gradually disappears, and I would argue, this is indeed what happened. Perhaps Bullinger never totally escaped from medieval Mariology, but his comments on the Assumption when placed in their historical context show that he may have been on his way.

Addendum 4/25/16 (18:30 PM)

One other primary source that I haven't completely worked through yet

is found here. The sermon appears to be from 1558, and

note the summary of this author claiming that Bullinger believed in Mary's Assumption based on the testimony of Eusebius. I'm in the process of working through Tappolet on this sermon as well. According to Tappolet's translation, the section in question mentioning Eusebius is very similar in content from the 1565 quote above. On page 293 in Tappolet, once again Bullinger's expresses a warning about it being dangerous to investigate or talk about what Scripture withholds. One should simply believe and confess Mary is heaven with Jesus Christ, not figure out how she arrived there. See

this part of the sermon in Latin:

Tapploet's German translation reads,

...über den Heimgang Mariens mit Verstand lesen, und alle lernen mögen, wie unfruchtbar und gefährlich es ist, neugierig zu forschen und darüber reden zu wollen, was uns in der Heiligen Schrift vorenthalten ist Es möge uns genügen, schlicht und einfach zu glauben und zu bekennen, daß die Jungfrau Maria, die liebe Mutter unseres Herrn Jesus Christus, durch die Gnade

und das Blut ihres eigenen Sohnes ganzgeheiligt und durch die Gabe des Heiligen Geistes überreich beschenkt und allen Frauen vorgezogen, und endlich, wie von den Engeln selber (p. 293).

That Tappolet doesn't include this in his section on Bullinger and Mary's Assumption (p.327-328) leads me to believe the author above interpreting Bullinger to be affirming the Assumption because of Eusebius is mistaken. Also that the author above omitted the warning passage in his synopsis leads me to conclude Bullinger may be being misinterpreted.