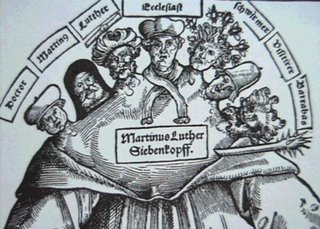

Above: One of Luther’s first Roman Catholic biographers was also a great adversary with lasting impact: Johannes Cochlaeus. Cochlaeus best expressed his campaign against Luther by portraying him as a seven-headed dragon. Cochlaeus divided up the life of Luther into seven distinct periods, each represented by one of the heads on the monster. Each head held a contradictory opinion to the other. He explains what each head represents:

“Thus all brothers emerge from the womb of one and the same cowl by a birth so monstrous, that none is like the other in either behavior, shape, face or character. The elder brothers, Doctor and Martinus, come closest to the opinion of the Church, and they are to be believed above all the others, if anything anywhere in Luther's books can be believed with any certainty at all. Lutherus, however, according to his surname, plays a wicked game just like Ismael. Ecclesiastes tells the people who are always keen on novelties, pleasant things. Svermerns rages furiously and errs in the manner of Phaeton throughout the skies. Barrabas is looking for violence and sedition everywhere. And at the last, Visitator, adorned with a new mitre and ambitious for a new papacy, prescribes new laws of ceremonies, and many old ones which he had previously abolished—revokes, removes, reduces.”

During Luther’s lifetime, one of Luther’s first biographers was also a great adversary with lasting impact: Johannes Cochlaeus. Cochlaeus spent a great deal of his life writing against Luther, and went so far as maintaining printing presses at his own cost to make sure his work was published. What makes this man interesting is that he was a contemporary of Luther’s, and actually had met Luther. His work is the immediate reaction of a Catholic scholar to the beginnings of the Reformation. The Catholic Encyclopedia says of him, “Naturally of a quiet and studious disposition he was drawn into the arena of polemics by the religious schism. There he developed a productivity and zeal unparalleled by any other Catholic theologian of his time.”

I have a growing collection of books by Roman Catholics written against Luther, and I actually tracked down an English translation of Cochlaeus’s magnum opus against Luther:

Commentaria de Actis et Scriptis Martini Lutheri (1549)

(The Deeds and writings of Martin Luther from the year of the Lord 1517 to the year 1546 related chronologically to all posterity by Johannes Cochlaeus)

I never thought I would hold this book in my hands. Here’s an interesting snippet from page one, speaking of Luther’s early life in the monastery before the 1517 posting of the 95 Theses:

“…[W]hen [Luther] was in the country, either because he was terrified and prostrated by a bolt of lightning, as is commonly said, or because he was overwhelmed with grief at the death of a companion, through contempt of this world he suddenly - to the astonishment of many - entered the Monastery of the brothers of St Augustine, who are commonly called the Hermits. After a year's probation, his profession of that order was made legitimate, and there in his studies and spiritual exercises he fought strenuously for God for four years. However, he appeared to the brothers to have a certain amount of peculiarity, either from some secret commerce with a Demon, or (according to certain other indications) from the disease of epilepsy. They thought this especially, because several times in the Choir, when during the Mass the passage from the Evangelist about the ejection of the deaf and mute Demon was read, he suddenly fell down, crying 'It is not I, it is not I.' And thus it is the opinion of many, that he enjoyed an occult familiarit with some demon, since he himself sometimes wrote such things about himself as were able to engender a suspicion in the reader of this kind of commerce and nefarious association. For he says in a certain sermon addressed to the people, that he knows the Devil well, and is in turn well known by him, and that he has eaten more than one grain of salt with him. And furthermore he published his own book in German, About the 'Comer' Mass (as he calls it), where he remembers a disputation against the Mass that the Devil held with him at night. There are other pieces of evidence about this matter as well, and not trivial ones, since he was even seen by certain people to keep company bodily with the Devil.”

Cochlaeus does what later Catholic critiques of Luther promise: to present the real “facts” about Luther, undistorted from Luther’s own writings. The Catholic Encyclopedia says Cochlaeus had no “effect on the masses”, but in actuality, his work did have a great effect on subsequent Catholic understanding of Luther. The Encyclopedia goes on to say that “His greatest work against Luther is his strictly historical "Commentaria de Actis et Sciptis M. Luther" (extending to his death), an armoury of Catholic polemics for all succeeding time.” The Encyclopedia also states that Cochlaeus is “in the main followed by Catholic investigators” doing research on Luther.

Cochlaeus, in essence, became one of Luther’s most influential opponents. His biography “deeply influenced the image of Luther held by Catholics for more than two centuries.”[17] His overall “image of the devilishly destructive Luther dominated Catholic popular understanding of Luther for centuries.”[18] The scholars agree:

“There can be no doubt of the sincerity and conviction of Cochlaeus, but neither can there be any doubt that it was he who poisoned the well of historical studies. Roman Catholic historians have drawn their prejudice against Luther from this polemical source, which in its animosity has an almost total disregard for objective truth and historical facts. Denifle, Grisar, Cristiani, Paquier, and Maritain (to cite the most famous and influential) have all drunk deep of this poisoned well-too deeply- and lesser historians have adopted their position.”[19]

“An answer to this question of why the more scientific and accurate Catholic depiction of Luther is so recent was well stated at the time of World War II by Catholic scholar Adolf Herte in a three-volume work, Das katholische Lutherbild im Bann der Lutherkommentare des Cochlaeus. His clear and, for many Catholics, embarrassing answer was this: Catholic Luther interpretation for the previous 400 years had more or less repeated what Johannes Cochlaeus, a contemporary of Luther, set forth in his extremely negative Commentaria de actis et scriptis M. Lutheri.. Cochlaeus' writings were basically nothing but fiction, calumny, and lies. In the rude style of that time, Cochlaeus depicted Luther as a monster, a demagogue, a revolutionary, a drunkard, and a violator of nuns.”[20]

No comments:

Post a Comment

You've gotta ask yourself one question: "Do I feel lucky?"