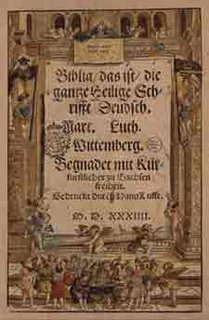

Above: Luther's German Bible

Above: Luther's German BibleOf all the things I’ve written, none has generated more interest and comment than my paper Luther's View Of The Canon Of Scripture.

Dr. Eric Svendsen graciously put this paper on his website: http://www.ntrmin.org/. For this I am very grateful. Ntrmin is a popular site, and its resources are some of the best there are. Both Dr. Svendsen and Jason Engwer are Godly men and capable apologists.

Occasionally, someone posts on a discussion board attempting to discredit this paper. Granted, I have found some typos, and the software I used for Luther’s Works did not function properly with some of the page numbers cited. Overall, I’m pleased with the paper, and the discussions usually don’t go very well for those I interact with about this subject.

Recently, I got an e-mail from a person named Malcolm critiquing this paper. I promptly wrote him back and let him know I would address his points on this blog. Malcolm, if you’re out there, this is for you.

Malcolm’s words will be in black, my words will be in blue.

***************

Malcolm says: “I found this article interesting. While Mr. Swan puts out the flames of some straw-man arguments, he obviously fails in his mission to rescue Luther.”

Swan replies: There was no “mission to rescue Luther.” My purpose was explicitly stated in the introduction:

“I thought it would be helpful to provide a brief overview of the most frequent Luther-related issues on the subject of the canon of Scripture. My goal is to encourage both Catholics and Protestants to at least seek to understand his view, even if one ultimately disagrees with it. Understanding Luther’s view of the canon is no small undertaking, nor do I claim to have successfully exhausted this topic or provided answers to every question. Understanding Luther on this issue demands approaching him from two perspectives:

1. Luther’s perspective on the canon as a sixteenth century Biblical theologian

2. Luther’s personal criterion of canonicity expressed in his theology

My primary focus will be on the first point since Roman Catholics tend to completely disregard it. Any attempt though to understand Luther’s view of the canon that neglects either of these is prone to distortion and caricature. My aim is not to develop excuses for Luther. You will find no argument in favor of removing James (or any other book) from the canon of Scripture. Here you will find no argument for Luther as an infallible authority. What I hope to present is Luther, a sixteenth century Biblical theologian and his concerns with the canon of sacred Scripture.”

Malcolm Says: “The point [James Swan] is dodging is whether Luther viewed the books in question as divinely inspired. Clearly, he did not, particularly in the case of James.”

Swan Replies: I did not “dodge” this. I explicitly stated: “Luther appears to have held lifelong doubts about the canonicity of James. In 1520 he wrote, “…I will say nothing of the fact that many assert with much probability that this epistle is not by James the apostle, and that it is not worthy of an apostolic spirit; although, whoever was its author, it has come to be regarded as authoritative.” Toward the end of his life in 1542, a Table Talk recorded similar sentiments.” I also stated that the evidence shows Luther’s opinions on Hebrews and Revelation fluctuated. It did not in the case of Jude.

Malcolm Says: “Yes, he included them in his Bible. But obviously did so for tradition's sake, similar to his inclusion of the "deutero-canonicals." However, his clear statement that James stood in contradiction to Romans and "all the rest of Scripture" indicates that he did not believe it to be divinely inspired or inerrant. Luther's own reasoning (shown in your coverage of Paragraph 3) clearly indicates this.”

Swan Replies: Well, then obviously Malcolm, I never “dodged” anything.

Malcom Says: “It is reported that his handwritten notes in James in [Luther's] own Bible includes indicating that one of the statements by James is simply wrong. Again, this indicates that he did not see it as divinely inspired or inerrant.”

Swan Replies: I have some transcriptions of the handwritten notes you’re mentioning (See J.M Reu, Luther And The Scriptures [Ohio: Wartburg Press,1944], p.42-43). I don’t recall anything like what you’re mentioning above. Perhaps you’re confusing this with a later Tabletalk entry in which he criticizes the simile in James 2:26 (see Reu, 43-44). It would be helpful to our discussion (and my research) for you to produce this information. While Luther's views on James can be criticized, at least stick with those you can actually prove. Attributing something to him you can't prove borders on slander.

Malcolm Says: “This position was obviously for public appeal. Simply put, for public consumption Luther held that the scriptures could include both divinely inspired, and non-inspired books due to public acceptance. He excluded the "deutero-canonicals" from these, because he could appeal to the Masoretic canon (an ironic appeal, considering Luther's anti-Semitism, and since late second century unbelieving Jews could not have been under the leading of the Holy Spirit). One might attempt to appeal to Luther's venire of graciousness as to how each person regarded these books. But this belies the fact that he himself did not view them as authoritative. It was a game of keeping the crowd. This was the same game Calvin played when trying to build a unified view of the Lord's Supper within Protestantism, forming a mediatorial view in hopes of building a unified front against Catholicism.”

Swan Replies: I must say, this is an amazing statement. It just goes to show, I haven’t heard it all. I’ve interacted with dozens of people critical of Luther’s view of the canon, and to my recollection, this is the first time someone has suggested that Luther was simply trying to gain public approval by stating Hebrew, James, Jude, and Revelation might not be Sacred Scripture, but included them in his Bible anyway. If you stop and think about what you’re saying, I hope you’ll see how silly it is.

Simply, Luther was honest about his views. You have to account for his usage of these books throughout his lifetime throughout his writings. If you really read my paper carefully, you would have noted that Luther preached from James, cited it approvingly, and did so with the other books in question as well. He did this both before and after the publication of his Bible. “Public appeal” was simply not an issue relevant to his views on the Canon. In my paper see specifically:

“6: Luther Cited And Preached From The Book Of James: The rarely documented positive usage of the Epistle of James by Luther.”

Malcolm Says: “Appealing to Cajetan cannot justify Luther's position against the vast majority of Church use since the fourth century. Further, there is a great deal of difference between questioning authorship, and questioning inspiration and authority. Many do not hold that Hebrews is of Pauline authorship, but they do not question its inspiration and authority.” Both can be wrong together. Appeal to Erasmus' view is under the general category of the Middle Ages is rather playing fast and loose with the truth. He was a contemporary of Luther's. This vouchsafes absolutely no credibility to Luther's view as being anywhere near standard. Erasmus was also a heretic, whom Luther's later repudiated."

Swan Replies: This is historical anachronism. The Renaissance caused all sorts of ripples in canonical issues. Cajetan, Erasmus, and Luther all approached the Canon as honest theologians. It’s very telling to me that Roman Catholics generally don’t criticize Cajetan or Erasmus on the canon. Nor do you really find any critical opinions of Cajetan’s views during his lifetime. A good student of the 16th Century knows how powerful and important a theologian Cajetan was, and how involved in the Papal machine he was. That these three men were three of the most famous theologians of the 16th Century should make you stop and think.

Malcolm Says: “Hardly a pictures of credibility. He also blows his credibility for not keeping in perspective that early canonical doubts for N.T. books had largely to do with lack of universal distribution (thus requiring the Council to investigate each). Further, his flagrant error of mistaking which James wrote "James" in his argument against Apostolic origin is such an amateur mistake, it seems likely that it was guided by his anxiousness to reject its authority due to his personal antipathy towards portions of it.”

Swan Replies: If these comments apply to Luther, again you’re perpetuating anachronism, because you assume to know what Luther should have known, rather than ask what was available to him. Jaroslav Pelikan has clarified, “According to [Luther’s] knowledge of early Christian literature, there was a sizable gap in time between the writers of the New Testament and the earliest church fathers. Luther regarded Tertullian, who died in 230, as the earliest writer in the church after the apostles…he apparently did not know the writers who later acquired the title ‘apostolic fathers.’ He was therefore, able to invoke the historical and chronological argument in a form no longer available to theologians of the twentieth century.” [Jaroslav Pelikan, Luther The Expositor (St. Louis: Concordia Publishing House, 1959), 84].

Malcolm Says: “Both by technical definition, and by evangelical viewpoint Luther stands as a heretic regarding canon, not to mention his view of Christ suffering for our sins in hell (ala the prosperity gospel folks).”

Swan Replies: Erasmus, Luther, and Cajetan formed their opinions and debated these issues previous to the council of Trent. The New Catholic Encyclopedia has honestly pointed out,

“According to Catholic doctrine, the proximate criterion of the Biblical canon is the infallible decision of the Church. This decision was not given until rather late in the history of the Church (at the Council of Trent). Before that time there was some doubt about the canonicity of certain Biblical books, i.e., about their belonging to the canon.”

If the New Catholic Encyclopedia is correct, Erasmus, Cajetan, and Luther had every right within the Catholic system to engage in Biblical criticism and debate over the extent of the Canon. All expressed “some doubt.” Theirs was not a radical higher criticism. The books they questioned were books that had been questioned by previous generations. None were so extreme as to engage in Marcion-like canon-destruction. Both Erasmus and Luther translated the entirety of Bible, and published it.

Malcolm Says: “The desire to uplift [Luther], and protect his saintly status in Protestantism is...perplexing. We the masses have obviously been sold a "bill of goods" on him; a load of p.r. hype and cover-up. "Luther, the great theologian!" What an embarrassment. Luther remains un-rescued.”

Swan Replies: I don’t view Luther as a saint, nor do I attempt to do anything else but treat him fairly. I’m not sure how familiar you are with Roman Catholic theologians, but many disagree with you: Luther was a great theologian. See my paper: The Roman Catholic Perspective of Martin Luther(Part Two)*. If you are a Roman Catholic, you may find this paper interesting.

James,

ReplyDeleteThis is very intereisting. I now have to go and read the original article.

I find Luther a fascinating fellow. He was greatly used of God and yet his own personality was destructive to the establishment of a unified Protestant front against the Rome.

Thanks for your work.

Dominus vobiscum,

Kenith

Hi Kenith

ReplyDeleteI plan on doing some posts on the Lord's Supper. I often wonder what could the Protestant Church have been like had they worked this out.

Thanks for stopping by.

Blessings-

fm483-

ReplyDeleteexcellent comments. Of course, The Roman claims for canon certainty are poor attempts of the theologians of glory. I've been through countless dialogs with them- showing them how their claims simply don't jive with history, and don't even jive with their own theology.

I think we can have a level of historical certainty that the Biblical books are reliable, and that they record accurate details, and were quite miraculously preserved.The church discovers canon, it doesn't create canon. There is no authority that has the capacity to declare God has spoken. God has spoken- no one stands above him to prove it to be true.

Ultimately, Christianity is accepted on faith. Sometimes theolgians downplay this. But really, to believe God spoke through a book is "foolishness".It is only they who's hearts of stone have been turned to hearts of flesh that hear the voice of God when reading the Bible.

I have a whole bunch of material on Luther and what he meant by "word of God". It's really interesting stuff. If I could blog all day, I would.

please I find ur comments very captivating.I want to know if martin luther's reformation was neccessary and justifiable and to what extent.

ReplyDeleteHi James,

ReplyDeletePlease I would like to know if luther's reformation was neccessary and justifiable.

thalnks.

Joshua Ukpore

Joshua-

ReplyDeleteYes, even Catholics now admit Luther had some valid points.